You may think that ticks die off with cold weather in the winter. A very cold winter means more ticks die off.

Many people still seem to have this notion but it’s not true. Ticks become dormant in the winter but don’t die off. Like most of nature, they are survivors and know how to do it very well.

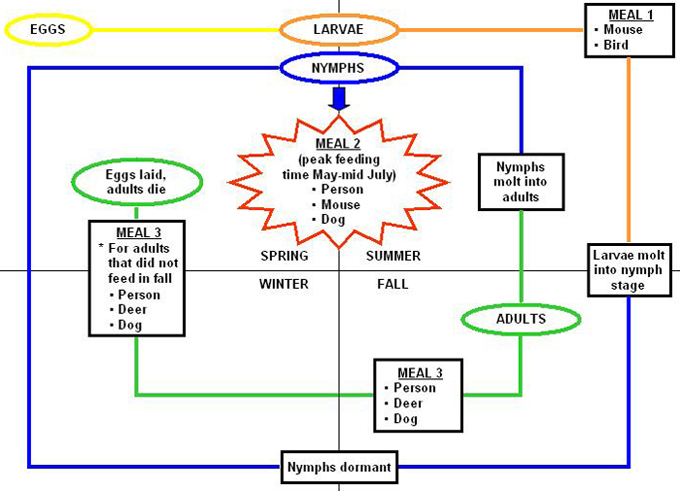

During a tick’s 2-year life cycle, they go from an egg to a larva in their first year of life.  Late in their first year, before winter, they are molting into nymphs. In order to grow from larvae to nymphs they need their first blood meal. Most will make this transition inside a white-footed mouse’s nest where they have warmth and an available blood supply to complete their transition into the nymph stage. Birds may also make a suitable blood meal for them before seeking the warmth of the mouse’s nest for winter.

Late in their first year, before winter, they are molting into nymphs. In order to grow from larvae to nymphs they need their first blood meal. Most will make this transition inside a white-footed mouse’s nest where they have warmth and an available blood supply to complete their transition into the nymph stage. Birds may also make a suitable blood meal for them before seeking the warmth of the mouse’s nest for winter.

The following spring they will be fully developed nymphs and begin looking for their next blood meal. It is at this time of the tick’s life that they are most likely to transmit Lyme Disease. The time of year is usually May through mid-July in MA.

Their very small size and need for a blood meal will require both male and female ticks to get that meal anywhere they can. They are able to hitch along on a mouse or human and continue to search for that blood meal until they have enough to molt again into an adult. Nymphs will quest at this time by reaching out from grass and bushes hoping to attach to a warm-blooded mammal like your dog, coyote, fox, raccoon, their friend the white-footed mouse or you.

In many areas, the white-footed mouse population is 85-90% infected with the Lyme bacteria. Taking a blood meal from an infected mouse in their nest guarantees the larvae tick or nymph tick is also infected with the bacteria. Voles, squirrels and other rodents may also serve as meals and many carry the Lyme bacteria.

Scientists have been working on how to interrupt this cycle of the larvae becoming infected in the mouse’s nest and eliminating them at that point, before they become nymphs in their second year. One effective method to do this is with tick tubes. Each fall, mice look for nesting material to build or refresh their nests. They need soft, lofty material in order to stay warm during the winter. Ticks need a place to hide and stay warm as well and the thick material and mouse’s body heat make an ideal winter home for them.

Reduce ticks in your yard now with tick control tubes.

Tick tubes are designed to provide the nesting material for the mouse. The cotton  material contains an insecticide that rubs on the mouse’s fur as it moves around in the nest. This insecticide is not harmful to the mouse. However, when a nymph tries to attach to the mouse for their blood meal it is prevented by the insecticide on the mouse’s fur. The tick dies and the mouse is unharmed. The net result is you have fewer ticks to deal with in your yard next spring and summer.

material contains an insecticide that rubs on the mouse’s fur as it moves around in the nest. This insecticide is not harmful to the mouse. However, when a nymph tries to attach to the mouse for their blood meal it is prevented by the insecticide on the mouse’s fur. The tick dies and the mouse is unharmed. The net result is you have fewer ticks to deal with in your yard next spring and summer.

Using both a perimeter spray and tick tubes are a double whammy to your yard’s tick population. Ticks that survive the winter, or are brought onto your property by other animals like raccoons, coyotes, fox, opossum, etc., are eliminated by the perimeter spray. An EPA-approved professional tick control barrier spray will be 85-90% effective against ticks. Adding tick tubes to your tick prevention program drops the total number of ticks down even before the spray is even applied the following spring. In the end you, your family and your pets have a lower risk for tick-borne infections while enjoying your yard next summer.

One thought on “Now Is The Time To Reduce Ticks In Your Yard Next Summer”

Comments are closed.